Manga is a unique historical document that depicts the life of the Japanese people

In the past, manga, anime, and video games were viewed as unimportant subcultures, but in recent years, they have been employed by the Japanese government and others on worldwide platforms as symbols of the country's soft might. In addition, the prices of some manga's original illustrations have risen to tens of millions of yen at international art auctions. How are these tendencies to be interpreted?

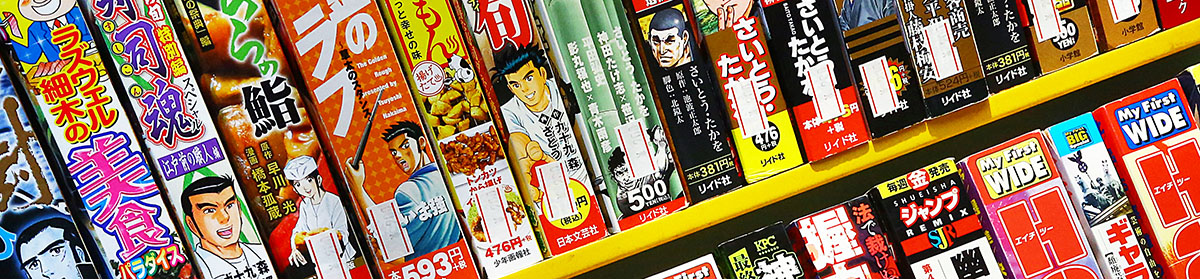

The evolution of manga in Japan has been unparalleled in other countries.

Since 2018, a new supply of resources for manga and anime historians has emerged, for better or for worse: Original drawings and images of Japanese manga and anime have begun to be sold for astronomical prices at Sotheby's, Artcurial, and other famous international auction houses.

Historically, such original drawings were exchanged in Japanese and foreign markets by art enthusiasts. This is how I obtained such materials for my research. Even in such markets, it was not unknown for prices in the millions of yen to be given for the original drawings of renowned animation directors, despite the fact that they were not intended to be artworks but rather manufacturing materials.

Upon entering the catalogues of major auction houses, the value of such original drawings and animation cels skyrocketed by an order of magnitude. In 2018, the British Museum hosted a comprehensive exhibition of Japanese manga, which may have contributed to the increase in speculative interest.

Numerous nations make graphic novels and animated features. From the mid to late 20th century, Disney's works were an integral aspect of America's cultural hegemony on the international stage. Since the 1990s, manga and anime have attained a comparable level of international visibility and cultural recognition. Theoretically, this was mostly attributable to their distinctive growth route, which was significantly distinct from Disney's works.

This change was largely a result of manga's expansion beyond children's audiences in Japan. With the exception of satirical drawings, manga was once primarily regarded as children's reading material in Japan. The situation was gradually altered by the postwar baby boomer generation. In 1959, when the boomers were in fifth or sixth grade, weekly comics for boys debuted. Such periodicals, which were particularly tailored to the generation at the time, were a whole new species. Coincidentally, two magazines, Weekly Shonen Sunday and Weekly Shonen Magazine, were released concurrently, resulting in competition.

The publications grew to represent a generational experience for the readers, and it was not uncommon for them to continue reading manga well into their adolescence. In the late 1960s, when this generation reached maturity, college students began reading manga magazines aboard trains, much to the chagrin of elder generations.

Historically, college students were viewed as considerably more privileged than they are today. Reading manga mags in public was also a fashion statement of the anti-establishment movement during the student uprising. The phrase "Holding [Asahi] Journal in one hand and [Weekly Shonen] Magazine in the other" depicts the prevailing sentiment of the era.

In contrast, Ashita no Joe, which was published in Weekly Shonen Magazine at the time, presented a nuanced portrait of its protagonist, who was raised in a slum, and a cynical view of his peers who blithely appreciated growing lifestyle fads. While miniskirts, "group sounds (rock bands)", "go-go cafes (discothèques)", and other youth culture were touted as the precursors of a new era alongside campus riots, manga magazines stood behind such youth culture and by the side of a large majority of youths and their sentiment when only one out of every five high school students went to college.

Then, in order to cater to the maturing readership, magazine publishers began releasing manga publications for young adults and businesspeople. By the time the baby boomers reached middle age, manga had become so popular and accepted in society that, for instance, Introduction to Japanese Economy à la manga became a best-seller.

Not forgetting, many girls' manga magazines sprang from prewar girls' periodicals. Manga for women became as popular as manga for males. The sheer volume of female-targeted manga creation is likewise unique to Japan and absent in other nations. Similarly to its counterparts for male readers, manga magazines for young women, "ladies' comics," and even manga magazines for middle-aged and elderly women were published.

The academic value of manga archiving in a methodical manner

As a result of these developments, Japanese manga has acquired an aspect of being a unique historical record of the Japanese people, having mirrored the changing ideals and lifestyles of every age-gender group during the postwar era. For instance, what did 1960s young women desire? How different was their view of the world from that of young boys of the same generation or young women of the 1970s ten years later? When they established a family in the 1980s, what sort of lifestyle did they adopt?

Manga has been seen as an unimportant subculture with a large number of undiscovered areas by professional scholars, despite the fact that manga has been admired by a wide variety of Japanese people throughout the years.

The National Diet Library does archive manga magazines and tankobon (independent volumes), although there are a considerable number of manga magazine issues that publishers neglected to provide to the NDL. In addition, the NDL archives all types of books after removing dust jackets, obi paper strips, and other book covers. As a result, the NDL-archived manga tankobon do not permit researchers to view the cover illustrations that consumers would have seen when looking for manga to read in a bookstore, let alone photocopy them. This presents a significant barrier to research referencing.

At the Manga Library, we save any cover, obi, and free premium item that was connected to the book or magazine when it was received. In addition, the library manages them without barcode labels or library stamps, and each collection is kept in an exhibition-ready condition.

The majority of the books and periodicals archived by the NDL were submitted through retail distribution channels. Rarely seen at the NDL are the once-popular kashihon (rental) manga, which circulated only through rental bookstores during the 1950s and 1960s, and the doujinshi (self-published) manga, which has served as a key basis of manga, anime, and gaming culture since the late 1970s. In fact, kashihon manga and doujinshi represent a significant component of our collection at the Mange Library at Meiji University. In this regard, our collection is particularly complimentary to the National Diet Library's.

The globalization of Japanese manga, anime, and video games

2009 saw the opening of the Yoshihiro Yonezawa Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures at Meiji University. Then, we declared our intention to use the Manga Library as a precursor to the eventual establishment of a larger, more complete archive museum covering not only manga, but also anime and video games.

Although there are already manga libraries, anime museums, and efforts to archive games in Japan and elsewhere, there are currently no full-fledged facilities with a framework that enables manga, anime, and games to be systematically archived and exhibited together to encompass their heavily interrelated cultural and industrial development in Japan.

Based on the popularity of manga in Japan, the international success of Japanese manga, anime, and video games stems from the diversity of their content. Through transmedia franchising, many of the genres and characteristics developed for this readership in manga were subsequently adapted for anime and video games, and vice versa. The comprehensive archiving of Japanese manga, anime, and video games is vital for both study and exhibition reasons, in order to analyze and demonstrate its international transcendence.

In sharp contrast to Disney's animated pictures, which are designed to be enjoyed by families, Japan has developed a large number of anime aimed solely at girls and young adults, based on a wide variety of manga created for a highly segmented audience. Unlike any Disney or Hanna-Barbera animated cartoon, titles such as Sailor Moon and AKIRA left a distinct imprint on audiences worldwide. Manga's widespread acceptance in Japan has resulted in an unprecedented expansion that has extended throughout the world.

In recent years, Japanese manga and anime have caught the attention of not only commercial firms but also local and national governments as significant cultural resources to develop the economy through inbound tourism.

Examples include the 18-meter-tall Mobile Suit Gundam statue installed in a public park as part of the Tokyo metropolitan government's campaign to bid for the Olympic Games, the inclusion of Captain Tsubasa and Doraemon in the video presentation, and the appearance of then-Prime Minister Abe in a Super Mario costume at the closing ceremony of the Rio Olympics to promote Tokyo as the next host city. Today, Japanese manga and anime are utilized in methods that were inconceivable when they were merely subcultures.

This international renown has also resulted in the high-priced trading of original drawings and the like at international art auctions, which I alluded to in the outset. There is a risk that the valuation of these cultural assets, which have been nurtured by the common people of our country, will be dominated by the principles of capitalistic speculation on the stage of international art auction houses and by the authority and interests of powerful museums abroad, where they may eventually land.

In this context, one of the most difficult aspects of the Meiji University project to construct an archive facility complex for manga, anime, and games is how effectively we can acquire and archive original drawings and the like in collaboration with artists, publishers, and production companies.